Last Updated on September 29, 2020

Shipping a box of frozen meat in the mail sounds simple enough, right?

Start with an insulated box, put some meat in, add some dry ice or other cooling product, and send it on its way.

For a number of reasons, shipping frozen steak, pork, chicken, and salmon is not that simple. Without knowing of an alternative, we initially rolled out our first steak orders packed in Styrofoam coolers — which were, at the time, the industry standard. From an environmental impact standpoint, we were not comfortable with Styrofoam and similar products. And so, from the beginning, we were determined to utilize a solution that combined sustainability with thermal performance.

This led us to roll out some incredible, sustainable alternative frozen shipping innovations; however, it also led to us learning some hard lessons when it comes to shipping frozen products.

Our cross-company dedication to relentless improvement led us to dig more deeply into solving these issues and, eventually, to our new revamped packaging design.

Our frozen shipping learning curve

I have been part of ButcherBox from its earliest days — as a college intern, I was part of the company’s Kickstarter launch. Since we launched the company to today, there have been two operational issues that have plagued our business. Looking back at the very first analyses of why members canceled — and then over time — two issues popped up again and again on why our members canceled their subscription:

- “Thaws,” orders that do not arrive frozen.

- “Leakers,” orders in which the meat’s packaging is either damaged or not fully sealed.

When dealing with perishable meat, neither thaws nor leakers are a preferable occurrence. More problematic is that the end result of both these issues is usually quite messy.

During the summer of 2018, member complaints about both our thaws and leaking packages went through the roof. Peak hot season was upon us and we were letting our members down with poor service. We were inundated with pictures like the one below — directly to our customer service and, worse, across social media — from unhappy members.

Although looking at the numbers, the frequency of leakers and thaws was relatively low, to us it began to feel like the norm.

Putting our mission of relentless improvement into action

We knew we needed to take a step back and re-evaluate everything we thought we knew about shipping frozen meat in the mail. During this time, we were fortunate to team up with a world-class cold chain partner who helped us to stop the bleeding — literally. Understanding that we had to solve this pain point for our members, they joined us in making a commitment to solving the thaw and leaker issues for the long term.

After months of back-and-forth projects where we experimented, tested, re-tested, made design changes, and tested again, this is what we learned.

Air is the enemy

When we first started shipping, we utilized a two-piece insulation product similar to the plastic-film covered you see in the top of this box:

(You can see a lot more examples of this insulation in the many ButcherBox “unboxing”videos on YouTube.)

The problem with this insulation solution was that it allowed for air to flow in and out of the box. We discovered that it was not uncommon for the insulation to be inserted incorrectly, shift during transit, or be poorly sealed on top. The result was warm air in, cold air out, and meat that looked like it had been left outside for the day.

Solution

As a response, our partner came up with a design to seal the insulation with an inner piece of corrugate. Version 1 of that design turned into V.2 that included a lid to seal the top. These two iterations on the box ended up restricting almost all air flow in and out of the box, which drastically improved the thermal performance.

One size does not fit all

Following up on our airflow lesson, we then learned that dead space inside the box was another true enemy of thermal performance. Up until this point, we had only utilized one box size to ship every order. It was a fairly standard square-shaped box that could be found in stock at almost every corrugate manufacturer.

It was a quintessential example of an operational assumption that we had never imagined questioning.

As we dug deeper into the box data and simulated pack outs, two things became clear:

1. We were shipping a lot of empty air.

2. Our “stock” box was not optimized for a wide variety of our orders and meat offerings.

Outside of being fairly illogical for these two reasons, empty space can create havoc on frozen meat.

Even with our collective B- knowledge of high school chemistry, we realized that conditioning a larger volume space with more oxygen flow requires more energy, which for our boxes just happened to be our dry ice. We quickly realized that the additional oxygen and air flow sped up the phase change of dry ice, causing it to melt quicker than we had anticipated and not keeping the product cold.

Solution

Why ship with one box when you can ship with four! The best way to solve for the wide variability in our orders and product offering was to increase the variability in our box offerings.

We designed four boxes specifically to minimize as much dead space as possible while accommodating a wide variety of orders and meat items. This led to a reduction in material waste and improved thermal performance. Most importantly, it creates a better experience for the member.

The meat must be cold — but not too cold

Some of you might be reading this and wondering, “If you had problems with the meat defrosting, why not just put more ice in?”

I can proudly tell you that yes, we did think of that! We followed the obvious solution of adding more dry ice, however, this led to another discovery: Additional dry ice helped to decrease our thaw rate, but it led to an uptick in our leaker rate.

This was an “AHA!” moment that ended up helping us with the problem of opened and leaking packaging that we thought was unsolvable.

Frozen film (our packaging) is not designed to be exposed to temperatures much more extreme than -20°F. When conducting testing, we realized that the -110°F dry ice was conditioning the meat packaging to temperatures that risked the film becoming brittle and cracking. We even explored gel packs, but then quickly discovered that they couldn’t satisfy our frozen requirements either.

It became a bit of a catch-22. Increase the dry ice, reduce the thaws, and increase the leakers, or decrease the dry ice, increase the thaws, and decrease the leakers.

We needed to find a way to keep the meat cold, but not too cold.

Solution

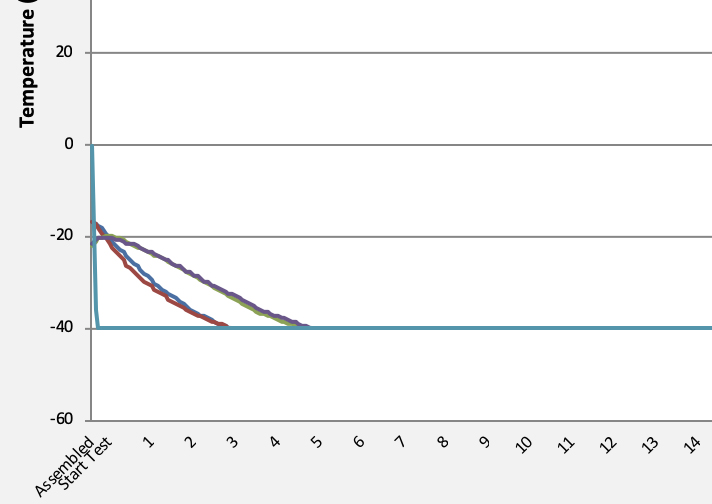

We tested protecting the meat and packaging from the extreme temperature of the dry ice with an insulated pad that sits between the meat at the bottom of the box and the dry ice at the top. Our thinking was that this would ensure enough coolant makes its way down to the meat, but not too much to push the meat and packaging past that -20°F breaking point. The two graphs below tell the story of how we discovered testing this approach.

Graph #1- Without Insulated Pad

Graph #2- With Insulated Pad

There is a stark contrast between the box with the separator and one where the dry ice is close to the meat. In the first, without the insulated pad, the temperature immediately dips below -40°F as there is nothing standing in between the meat and the -110°F ice. However, in the second graph, the small change of adding the insulated pad prevents the meat from dipping below -20F and keeps it away from the danger zone.

Our work is never done

All of this testing and learning led to the development of a curbside recyclable box that is being used to ship steaks, bacon, pork butts, and salmon to ButcherBox members on the East Coast. Even better, we are in the process of transitioning our entire shipping network to this new improved box just in time for the peak hot season this summer.

Our new packaging solution is just one of the ways we hope to give our members the best possible experience. This is being coupled with exhaustive work from our logistics team to proactively manage our shipping network and develop dry ice formulas to improve the entire delivery experience. However, the greatest lesson that we have learned throughout this entire experience is that our work is never done. There are more innovations to discover and more improvements that can be made.

We have not fully perfected how to ship frozen — and we may never achieve that lofty goal — but we are going to continue to relentlessly work to get as close to perfect as our members deserve.

Bobby Quirk works on the Operations and Procurement Team at ButcherBox.